When I was in college, a classmate from my preschool days wrote to me on Facebook. I had absolutely no memory of this person, but they gushed about how memorable I was. Then they sent me a photo of our class. I was stunned.

There I was, grinning amongst the other kids in the “special ed” group. I was never in a class of this kind, I would have sworn on it. A class with no desks or structure, a class submerged in chaos, feeling kinda institution-y… I kept wondering, "How did I even get in this photo?"

I remember riding the short bus. I remember climbing the stairs in elementary school because there were no elevators. And I remember being a college-bound senior removed from my classes to take tests on shapes and basic numbers to ensure that my no-legs didn't mean I had no brain. But I also remember always being in typical classrooms… or so I had thought.

President George H.W. Bush signed The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) on July 26, 1990, which means that for the first nine or so years of my life, I would have attended school without protection from discrimination based on my disability. That also means my school district would have taken one look at my wheelchair and–by default–banished me to the basement with all the other kids with disabilities, segregating us from the rest of the school.

Now in its 33rd year–and me in my 40th–the history of the ADA and its developers has been hitting me hard, namely because 2023 marks the first year we’ll celebrate the legislation without Judy Heumann, widely known as the mother of the disability rights movement and of the ADA itself.

Heumann Being

Heumann’s 75 years of influence on disability dignity and legislation is undeniably massive. Thinking about the ADA and disability civil rights without also thinking about her life and work would be akin to imagining the women's rights movement without Gloria Steinem. Maybe we would have gotten there without her, but we didn’t, and it would be hard to imagine we could have progressed otherwise.

To learn about Judy Heumann’s life is to also learn about the birth of the ADA–they are inextricably linked. For that reason, in this section, I lean on her memoir, my crip bible, Being Heumann: An Unrepentant Memoir of a Disability Rights Activist, which she wrote along with Kristen Joiner.

Born in Brooklyn in 1947, Heumann contracted polio and became a full-time wheelchair user and quadriplegic at a very young age. Deemed a “fire hazard,” she wasn’t allowed in schools until she turned nine years old.

After being waitlisted, evaluated, and approved (in order to go to public school–can you even imagine?!) she eventually won a grant called Health Conservation 21–a grossly performative program to get kids with disabilities into schools. In actuality, the school clustered her and all of the other disabled kids into one group–regardless of age or learning levels–and then sent them to the basement. Wondering what the kids upstairs were doing, the students of Conservation 21 were provided no avenue or expectation to learn, progress, or actually obtain an education.

The only saving grace is that some of these kids began to talk, bond, and eventually end up at Camp Oxford. The camp, featured in the Obama Netflix film Crip Camp, allowed kids with disabilities to act with freedom, autonomy, and abandon. For the first time in their lives, they were finally able to be kids–not despite their disability, but including it. They played music, made out with each other, and moved around in a world where their needs were built-in and access was a given, where dignity wasn’t only integrated, it was integral.

Heumann and most of the kids from the camp ended up in Berkeley, CA at the Center for Independent Living (CIL), which she eventually ran. The camp and the CIL taught her and the crip community that access wasn’t impossible and their exclusion from society was not about their bodies but about the world in which their bodies lived.

After attending college, Heumann sued New York City’s Board of Education because they refused to grant her a teaching license, stating that she was unable to prove she could walk and that she refused to perform for a medical examiner how she used the bathroom. (Again, can you EVEN?)

She eventually won the hard-fought case, gaining the attention of the media and other civil rights organizations. She appeared on the cover of TIME magazine during a period when ugly laws–laws that barred those with disabilities from public life for “unsightliness”–were just being repealed.

These and other experiences eventually led Heumann to D.C., where she discovered a tiny piece of unsigned regulation strategically hidden in The Rehabilitation Act. The clause, called Section 504, prohibited the discrimination of people with disability in education, work, and other government-funded organizations. After waiting for three presidential terms, she and her crip-camp family, along with hundreds of others, camped out for 28 days until President Jimmy Carter signed the legislation, unchanged, on April 28, 1977.

The Birth of the ADA

I'm very honored and proud to be celebrated with this auspicious group of women leaders @TIME https://t.co/NQVwuSr38G

— Judy Heumann (@judithheumann) March 6, 2020

From that day on, it was technically illegal in public spaces to discriminate based on disability. But the law wasn't being enforced, and it didn't cast a wide enough net. Time and time again, the government evaded the regulations of the bill and refused to honor its presence.

That’s when the ADA was imagined, partly by Heumann and her camp friend/colleague, Ed Roberts, along with a few Republicans–wild, right?

After fighting a decade-long battle to shape and sign the ADA, in July of 1990 Congress finally passed the bill. Heumann spent the rest of her life working for the Clinton and Obama administrations, along with the World Bank, a financial institution that lends money to developing countries and researches ways to end poverty, to improve the ADA and to ensure it remained enforced and globally recognized.

Even though today’s crips, including myself, have emerged in a much different landscape, I still recognize myself in Heumann’s story: her gumption, her anger, the way she endured unjust demands to prove her humanity over and over. All of which leads me to wonder about Heumann and her legacy: Aren’t we still fighting for those same things? What’s the same? What’s different?

So here is my take on the ADA–then and now–from the perspective of a baby Gen Xer who remembers life before the ADA but who largely identifies with the ADA Generation, a group that doesn’t know of a life without it and considers its presence a birthright.

The Fight Ahead

If we want access, then we still gotta ask for it. The ADA is a reactionary–not a preventative–law. That means the burden of access remains on the community facing discrimination. All you haters who like to proclaim that people with disabilities take advantage of business owners for money like some kind of yucky hustle should recommend some other way to secure our rights, because right now there is no ADA police. Making a stink is all we got. It’s all we’ve ever had.

All the ramps aren’t built and all of the elevators aren’t in. Me and my fellow folks with disabilities will unequivocally tell you that issues of accessibility remain ever-present. But there are several kinds of structural ableism: I like to think of it as annoying versus prohibitive access.¹

- Annoying Access is when you have to go around the block or through the back… it's annoying and othering, but it's still do-able. It's like when only a fraction of curb cuts are on our sidewalks. Imagine the four corners of a block and only one or two of the easements are accessible. Ramps that lead to curbs negate access, and it's annoying.

- Prohibitive Access is when you can’t get in, there is no access. It's more than annoying, it blocks you from participating in public life and it’s discrimination. One example is the historical building clause, which is part of the ADA stating that structures built before the ADA are not required to make their spaces accessible to people with disabilities… ever! That means physical barriers to access for people with disabilities will never progress past any improvements made by the 1990s. That's like saying computer systems should have halted at DOS. Why?

We still hold significantly fewer jobs. The rate of employment for persons with a disability is 21% compared to 65% for persons without a disability, according to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Moreover, people with disability are the only group of people who can legally make subminimum wages. And people of color with disability are disproportionately marginalized in terms of health care, education, and in careers at a staggering, heartbreaking rate of 18%. Speaking of things that disproportionately affect POC…

People with disability are blocked from acquiring wealth. Wage caps exist for most disability-related insurances, such as Medicaid and Obamacare. Those programs will not cover things like adaptive devices, medications, and/or personal assistants if you make slightly less than the poverty line, creating a system of poverty that few escape. I stopped accepting my government help at the age of 19 and have accrued astronomical bills for any and all adaptive devices ever since. This is why I, like Beyonce, believe that “the best revenge is your paper.”²

Airplanes are still not covered by the ADA. Congress passed the Air Carrier Access Act before the ADA, and because of this air travel was not included under the umbrella of the ADA. The impact is beyond staggering. Airlines destroy wheelchairs at a rate of 28 PER DAY, as reported by the Department of Transportation. A year ago, a disability rights activist DIED as a result of being mishandled on a plane. If you want to know more, go check out a piece I did with VICE about how flying with a disability is the most dated, dangerous, and undignified experience of modern disabled life.

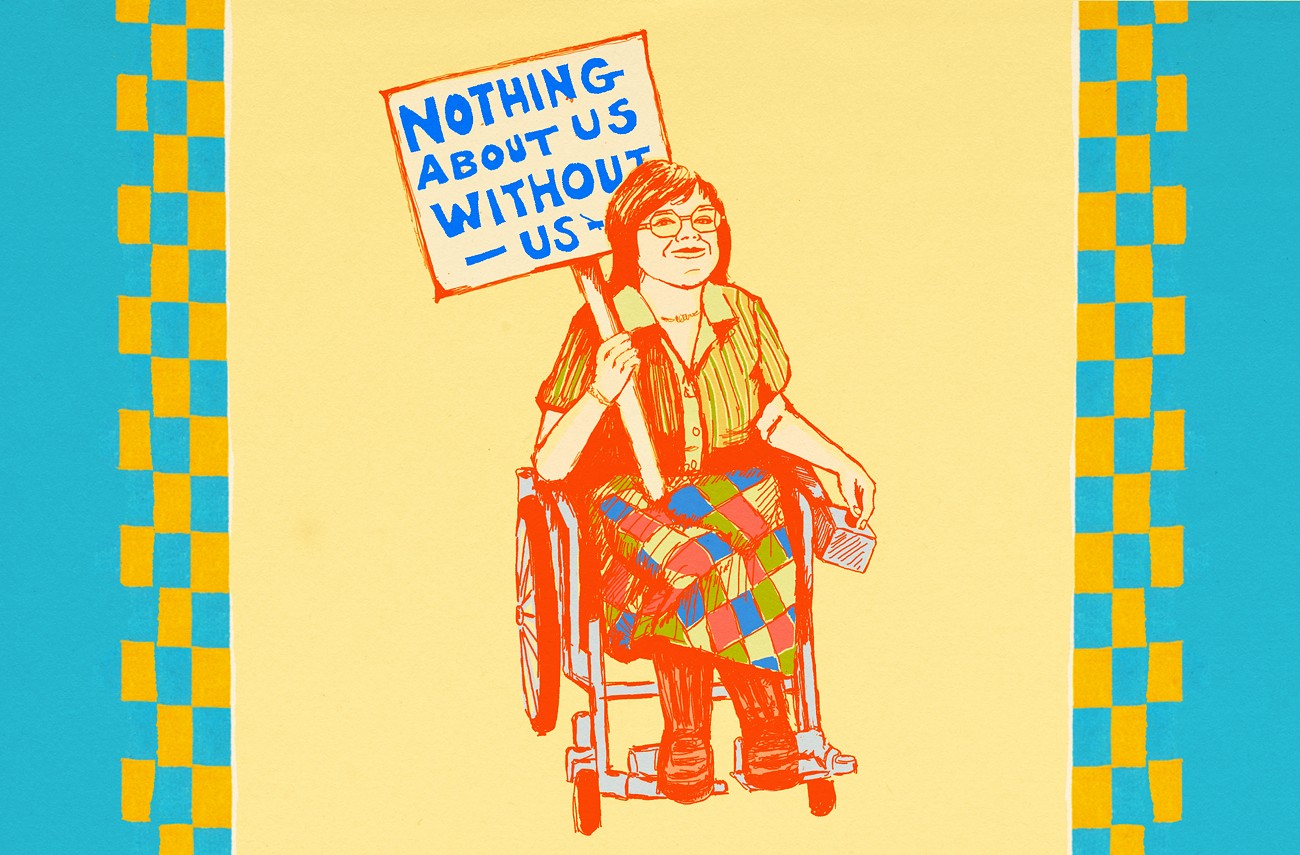

Representation matters. Although people with disability are the most mis- and under-represented population in the media, we have more icons of disability than ever before. Crips invented the phrase nothing about us without us, and it remains our biggest challenge. Disability representation and equity within the arts remains largely ignored in practice, so our stories lack complication and our jobs in these spaces remain bottom-tier or performative at best. Not to mention, the actual stages and venues remain largely inaccessible to performers and patrons with disability.

The ADA must be updated often. Disability and our world are ever-evolving. The ADA could not have anticipated tech-boom dilemmas such as Uber. Ride-shares are still completely inaccessible outside of three major US cities. In addition, virtual spaces are all but unregulated by the bill, leaving out an entire sector of public life for people with disability.

The ADA generation is here and proud of our crip identity. Twenty million young people grew up knowing the ADA as a birthright. The law's passage did a lot for the dignity and self-value for 20% of the world’s population. To us, the ADA says, “We see you as humans beings,” and we didn’t have to hide anymore. The stigma, which is still very present, was in some ways lifted. Crips today are quick as hell to claim, “We’re here, we’re proud of our identity. We are the 20%—impossible to ignore.” That said, we believe the ADA to be the bottom tier of what disability justice really looks like. We want more.

¹ These examples, and my experiences reflect a life with physical disability and being a wheelchair user. But disability goes far beyond my experiences and includes myriad access, adaptations, and disability presentations. Many of those aren’t “physical” and remain not apparent. But the experience of being denied access is ubiquitous for all people marginalized by disability.

² That is my privilege, and I recognize how most of my crip siblings are not afforded the luxury of accruing wealth.