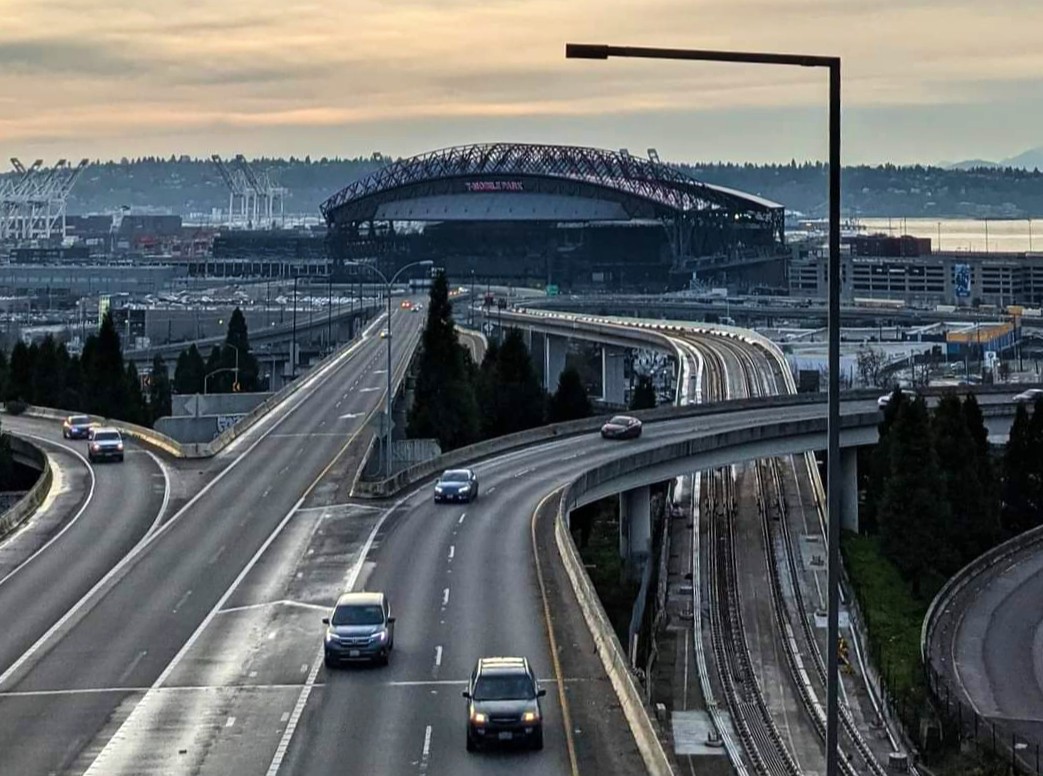

This has a familiar ring to it. Seattle today; Harare yesterday. The former concerns the 2023 MLB All-Star Game; the latter Pope John Paul II's 1988 visit to Zimbabwe, which, at the time, was one of the Frontline States. My age: 19; my situation: Preparing to leave the 9-year-old country (it was born in 1980). Indeed, at the time, I spent most of my time not in the House of Stone (Zimbabwe) but instead in Botswana—in 1987, my mother, a professor, closed her five years at the University of Zimbabwe with a post at the University of Botswana. This was a happy period in my life. The poverty in Botswana was nowhere near as desperate as that found in Zimbabwe, a poverty that seemed to have no beginning or ending, a poverty that made me feel like the survivor of a plane crash: "How am I alive?" was the same as asking "How am I not poor and miserable like everyone else?" And it was this near-universal and always heartbreaking misery that the corrupt Zimbabwean government abruptly and successfully removed from the streets of Harare (the capital of Zimbabwe) for Pope John Paul II's visit. Beggars, hawkers, hookers, and others found at the bottom of the hoi polloi, were swept out of the city's center. The pope only saw spick-and-span people and streets from his bulletproof popemobile.

You can see where this is going. Seattle is doing the same thing in 2023. This time it's not a pope, but the gods of professional sports.

Cleanup is set for a row of RVs that some say has been the source of safety concerns and problems in Seattle’s SODO neighborhood.https://t.co/GRWU8LTDjW

— KOMO News (@komonews) February 9, 2023

What can we make of this connection? One of the richest cities in the world is doing exactly the same thing that one of the poorest cities did decades ago? Zimbabwe's GDP in 1988 was roughly $8 billion ($20 billion in today's money); the current GDP for the Seattle area is around half a trillion dollars. Zimbabwe had a population of 10 million when the pope paid a visit; during the All-Star games, Seattle's metropolitan area has a population of 4 million. Sure, Harare's sweeping was considerably harder than Seattle's, but the principle is the same. And as such is the case, we must ask: How can there be so much wealth in Seattle and still lots of people for Bruce Harrell to sweep this way and that?

City of Seattle placed ecoblocks to stop the homeless from parking their broken down RVs around the stadium for All-Star Week.

— Jason Rantz on KTTH Radio (@jasonrantz) July 6, 2023

When businesses did the SAME thing to keep RVs away, @MayorofSeattle Harrell called for biz to be ticketed, and said “eco-blocks are just not the way.” pic.twitter.com/UQ5jZpCd0F

Now imagine if I went back in time, and told Harare's hoi polli—many of whom had fought a long and bloody war for the independence of their country, the Second Chimurenga—that even if the government expanded the economy from a puny $20 billion to a staggering $500 billion, many of you would still be struggling to pay rent or living on the streets. Even my imagination, which is pretty vivid, cannot picture their astonishment at these words. Many might even call the police on me for trying to spread this craziness in public. I can even picture a constable chasing me on an iron horse, yelling, between whistleblows: "You stop right now. Stop! You must be arrested for trying to make hardworking people lazy. They will not want to work if they believe the dangerous things coming from your mouth. You disturber of the peace. Stop!"

"Let's make sure their work was for nothing"

— Jeremy Harris (@JeremyHarrisTV) July 5, 2023

RV encampments have been ordered to leave SoDo in preparation for the All-Star game. I went to an encampment there yesterday and a guy gave me this flyer that he says a group came around passing out. https://t.co/loeXjwKM0h @komonews pic.twitter.com/Odo7vevaq1

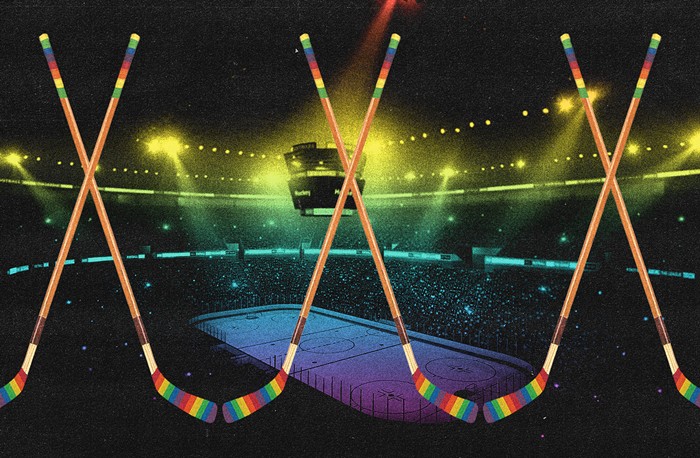

But how strange the god of Zimbabwean Christians is from the gods of All-Star games. The former promises the poor a gated community in the sky when they die ("...no more crying there, we are going to see the King / no more [rich people] people there, we are going to see the King"). The latter offers the only happiness authorized by capitalism, compensatory consumption. Because the explanatory power of this term, first introduced in 1988 by the French social theorist André Gorz, and revived during the short lockdown by the British-American geographer David Harvey, is considerable, it deserves a little space in this All-Star games post.

From Gorz's masterpiece Critique of Economic Reason:

Compensatory goods and services are, therefore, by definition, neither necessary nor even merely useful. They are always presented as containing an element of luxury, or superfluity, of fantasy which, by designating the purchaser as a 'happy and privileged person', protects him or her from the pressures of the rationalized universe and the obligation to conduct themselves in a functional manner. Compensatory goods are therefore desired as much - if not more - for their uselessness as for their use value; for it is this element of uselessness (in superfluous gadgets and ornaments, for example) which symbolizes the buyer's escape from the collective universe into a haven of private sovereignty.

Harvey adopted and updated this concept by adding an existential dimension. The past decade or so has experienced the rise of event-based capitalism. For example, according to Harvey, "[i]nternational visits increased from 800 million to 1.4 billion between 2010 and 2018." This form of consumption makes the right kind of magic in a society that, in essence, has way too much stuff. Those who sell forks or bricks or computers or gigantic pickup trucks are in a much weaker position, in terms of turnover, than those who sell things people can't take home. Once you have consumed a baseball game, it's over forever. These gods vanish.

If the concept of experiential capitalism is grasped, then this phenomenon is made clear:

Now, as Variety reports, Ticketmaster is defending the whole Springsteen debacle, claiming that only 11% of the tickets sold last week were at the “platinum” price and only 1% were $5000 or more. The company then went on to claim that the average Springsteen ticket sold for around $300 – which is still expensive, albeit not used-car expensive.

Harvey also points out that one of the key crises capitalism faced during the lockdown was exactly in this sector, the experience sector. Social distancing made this form of consumption ("airports and airlines, hotels and restaurants, theme parks... cultural festivals, soccer and basketball tournaments, concerts, business and professional conventions") impossible. And that's why there was greater pressure from the top to end the capital-killing lockdown, end mask-wearing, and return to people-packed ships and stadiums as if the pandemic was over. We not only live in the age of necro-economics but also event capitalism.